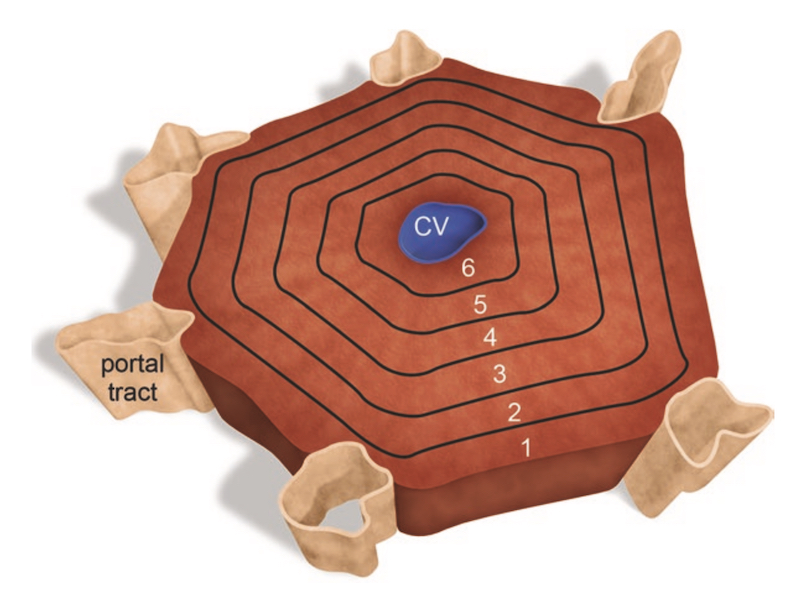

Abstract: The liver is a major metabolic organ, and the first site of contact of xenobiotics follows oral ingestion or administration. The primary functional unit of the liver is the hepatic lobule. Gradients for metabolizing enzyme and oxygen tension in the hepatic lobule determine toxification and detoxification of ingested xenobiotics with immediately toxic agents causing cell damage in the periphery of the hepatic lobule, while enzymatic generation of toxic metabolites typically affect centrilobular hepatocytes. A wide spectrum of spontaneous degenerative changes occurs in the liver, some changes are age-, species-, and strain-dependent, and the job of the pathologist is to assess the significance of a potential treatment-induced liver changes against the background changes in a particular study. Because the liver has a high regenerative capacity following insult, proliferative changes, including benign and malignant neoplasms, are common, especially in the rodent liver. These proliferative changes also occur with an age-, species-, and strain-related background, and the pathologist must weight any proliferative response against this background incidence. Unique to the liver is a class of proliferative lesions designated as foci of cellular alteration which are localized presumptively preneoplastic responses. Several cell types in addition to hepatocytes are present in the liver, and each needs to be addressed by the pathologist in safety assessment of liver changes. Key to understanding the judgment involved in documenting and categorizing the broad spectrum of liver lesions is the pathology narrative where criteria for assessing hepatopathology is spelled out by the pathologist.